Some have contended that shot placement is the most important parameter in determining the lethality of a bullet. Shots to the central nervous system and major blood vessels are the primary forms of incapacitation. Difficulty at range can be attributed to training, as only a few nations taught shooting beyond 200–300 meters to regular soldiers. Sweden and Canada had requirements to shoot 3-5 rounds, respectively, in the prone or kneeling position at 100 meters with a max dispersion of 150 mm (5.9 in).

Due to their inability to adjust rifle fire for dispersion, target movement, unknown ranges, and wind drift, Swedish ISAF units relied on .50 BMG heavy machine guns for long-range. A barrel length reduction of 59 percent results in a reduced muzzle velocity for 5.56 NATO ball of only 21 percent. The length differences between a 20 in M16 barrel and 14.5 in M4 barrel results in a trajectory difference of 16 mm (0.63 in) at 250 m. A bullet fired from an M16 has a greater striking velocity than one from an M4 only up to 50 meters longer distance.

Time of flight difference from the two barrel lengths is 2 cm (0.79 in) per meter per second at 300 meters. Underperformance can be attributed to errors in range estimation, target lead, wind, firing position, and stress under fire, which are factors that can be resolved through training. The 5.56×45mm cartridge, along the M16 rifle, were initially adopted by U.S. infantry forces as interim solutions to address the weight and control issues experienced with the 7.62×51mm round and M14 rifle. At those speeds, factors like range, wind drift, and target movement would no longer affect performance.

Several manufacturers produced varying weapons designs, including traditional wooden, bullpup, "space age," and even multi-barrel designs with drum magazines. All used similar ammunition firing a 1.8 mm diameter dart with a plastic "puller" sabot filling the case mouth. While the flechette ammo had excellent armor penetration, there were doubts about their terminal effectiveness against unprotected targets. Conventional cased ammunition was more accurate and the sabots were expensive to produce. The SPIW never created a weapons system that was combat effective, so the M16 was retained, and the 5.56 mm round was kept as the standard U.S. infantry rifle cartridge. Since its introduction, the M855A1 has been criticized for its St. Mark's SMP842 propellant causing increased fouling of the gun barrel.

Post-combat surveys have reported no issues with the EPR in combat. A series of tests found no significant difference in fouling between the old M855 and the M855A1. However, manufacturers have reported "severe degradation" to barrels of their rifles using the M855A1 in tests. The Army attributes pressure and wear issues with the M855A1 to problems with the primer, which they claim to have addressed with a newly designed primer.

During Army carbine testing, the round caused "accelerated bolt wear" from higher chamber pressure and increased bore temperatures. Special Operator testing saw cracks appear on locking lugs and bolts at cam pin holes on average at 6,000 rounds, but sometimes as few as 3,000 rounds during intense automatic firing. Firing several thousand rounds with such high chamber pressures can lead to degraded accuracy over time as parts wear out; these effects can be mitigated through a round counter to keep track of part service life. The U.S. has developed the Mk 262, Mk318, and M855A1 to give better performance from short barreled carbines, improve barrier penetration, and give more reliable terminal effectiveness. However, they have similar exterior ballistics to the M855 and do not meet the need for long-range coverage, as the rounds are limited by the small size and power of the cartridge.

Furthermore, the open-tip designs and fragmentation ability of the rounds may not be accepted by other NATO countries due to their interpretation of Declaration III of the Hague Convention. Another way would be to return entirely to the 7.62×51mm cartridge. The principle 7.62 round is the M80, which delivers terminal effectiveness through its size and power. It does not yaw rapidly on impact and although it has a longer range, it has poor long-range performance due to its relatively light bullet, which sheds velocity quickly. A low-recoil loading could be adopted for rifles, like the 138 gr (8.9 g) bullet used in the Japanese Howa Type 64, while keeping full-power M80 rounds for machine guns and marksman rifles.

The open-tipped Mk319 loading has good terminal effectiveness and barrier penetration, but greater weight and recoil still limits the usefulness of 7.62 mm rounds. Another option would be to keep the 7.62 for long-range use, and replace the 5.56 for short to medium-range use. The 6.8×43mm SPC has better terminal effectiveness and barrier penetration with little increased weight or recoil. The 6.8 mm round was kept short and relatively light to keep its overall length the same as the 5.56, so longer-range performance is limited.

The first prototypes were delivered to the government in August 2007. Increased velocity and decreased muzzle flash were accomplished by the type of powder used. The design of the bullet was called the Open Tip Match Rear Penetrator . The front of it is a hollow point backed up by a lead core, but the lead core only goes about halfway down the length of the bullet, while the rear half is solid brass.

When the bullet hits a hard barrier, the front half of the bullet smooshes against the barrier, breaking it so the penetrating half of the bullet can go through and hit the target. With the lead section penetrating the target and the brass section following, it was referred to as a "barrier blind" bullet. Special Forces role in counter-terror operations allow them to follow certain law enforcement guidelines, so they could use hollow point rounds without violating the Hague Convention. Hit probability refers to a soldier being able to concentrate on stance, weapon control, aiming, and trigger pull in spite of their weapon's recoil and noise, which has a noticeable difference between the two cartridges.

While the 7.62 mm has twice the energy of the 5.56 mm, it is only required if the target is protected by armor. Both rounds will normally pass right through an enemy out to over 600 m. A 5.56 mm round fired from a 20 in barrel has a flatter trajectory than a 7.62 mm round from the same barrel length. A 7.62 mm round from a 20 in barrel has the same trajectory as a 5.56 mm round fired from the 14.5 in barrel of an M4. A typical 7.62 NATO-chambered weapon has a barrel length of 20 in, and reaches half of its velocity after 3 in of travel down the bore. Shortening the barrel for close-quarters use results in decreased muzzle velocity and increased muzzle pressure.

If the 5.56mm bullet is moving too slowly to reliably fragment on impact, the wound size and potential to incapacitate a person is greatly reduced. There have been numerous attempts to create an intermediate cartridge that addresses the complaints of 5.56 NATO's lack of stopping power along with lack of controllability seen in rifles firing 7.62 NATO in full auto. Some of alternative cartridges like the 6.8mm Remington SPC focused on superior short-range performance by sacrificing long-distance performance due to relatively short engagement distances typically observed in modern warfare.

Others, like the 6.5mm Grendel, are attempts at engineering an all purpose cartridge that could replace both the 5.56 and 7.62 NATO rounds. The 300 AAC Blackout (7.62×35mm) round was designed to have the power of the 7.62×39mm to use in an M4 platform using M4-type magazines. None of these cartridges gained any significant traction beyond sport shooting communities.

While both the 6.8 SPC and 6.5 Grendel perform better than the 5.56 NATO, they have their own drawbacks, including lower muzzle velocity and decreased magazine capacity. The 6.8 SPC's short and light bullet has poor long-range ballistics and a poor ballistic coefficient, and the 6.5 Grendel's case has poor ergonomics and a larger case diameter. The 5.56mm NATO chamber, known as a NATO or mil-spec chamber, has a longer leade, which is the distance between the mouth of the cartridge and the point at which the rifling engages the bullet.

The .223 Remington chamber, known as SAAMI chamber, is allowed to have a shorter leade, and is only required to be proof tested to the lower SAAMI chamber pressure. To address these issues, various proprietary chambers exist, such as the Wylde chamber or the ArmaLite chamber, which are designed to handle both 5.56×45mm NATO and .223 Remington equally well. The leade of the .223 Remington minimum C.I.P. chamber also differs from the 5.56mm NATO chamber specification. If the 5.56 mm bullet is moving too slowly to reliably yaw, expand, or fragment on impact, the wound size and potential to incapacitate a person is greatly reduced. Others, like the 6.5mm Grendel (6.5×39mm), are attempts at engineering an all purpose cartridge that could replace both the 5.56 and 7.62 NATO rounds.

All these cartridges have certain advantages over the 5.56×45mm NATO, but they have their own individual tradeoffs to include lower muzzle velocity and less range. Additionally, when using a round not based on the case of the 5.56 there can be decreased magazine capacity, and different internal parts. None of these cartridges have gained any significant traction beyond sport shooting communities.

The 5.56×45mm NATO standard SS109/M855 cartridge was designed for maximum performance when fired from a 508 mm (20.0 in) long barrel, as was the original 5.56 mm M193 cartridge. Experiments with longer length barrels up to 610 mm (24.0 in) resulted in no improvement or a decrease in muzzle velocities for the SS109/M855 cartridge. Unless the gas port can be regulated or adjusted for higher pressures, suppressors for short barreled 5.56×45mm NATO firearms must be larger and heavier than models for standard length rifles to function reliably.

The reverse of this is firing a 223 Rem cartridge in a 5.56 NATO chambered rifle. Due to the throat difference between the two chambers a 223 Rem cartridge may not work optimally in a 5.56 NATO chambered weapon. The cause of this is the lack of pressure built by a 223 Rem cartridge fired from a 5.56 NATO chamber.

The 223's 55,000 psi will not be attained and therefore velocity and performance are hurt. Problems start occurring when this combination is fired out of a 5.56 NATO chambered rifle with a 14.5" barrel. The lower powder charge of the 223 round coupled with the pressure drop that occurs when it is fired in a the 5.56 NATO chamber will cause the rifle to cycle improperly. NATO chambered rifles with barrels longer than 14.5" should function properly when firing 223 Rem ammunition. In 1999, SOCOM requested Black Hills Ammunition to develop ammunition for the Mk 12 SPR that SOCOM was designing. The problems were addressed with a slower burning powder with a different pressure for use in the barrel, creating the Mk 262 Mod 1 in 2003.

During the product improvement stage, the new propellant was found to be more sensitive to heat in weapon chambers during rapid firings, resulting in increased pressures and failure to extract. This was addressed with another powder blend with higher heat tolerance and improved brass. Also during the stage, Black Hills wanted the bullet to be given a cannelure, which had been previously rejected for fear it would affect accuracy. It was eventually added for effective crimping to ensure that the projectile would not move back into the case and cause a malfunction during auto-load feeding.

Although the temperature sensitive powder and new bullet changed specifications, the designation remained as the Mod 1. When comparing .223 and 5.56 ammo, they look almost identical in size and shape, but on the inside of the casing, they're different. With different bullet weights, powder loads, and chamber pressure, the 5.56 NATO is a more powerful force and is often considered a .223 +P. In addition to these configuration differences, .223 rounds have a shorter leade .

In most cases, it is safe to shoot .223 ammo from a rifle chambered for 5.56 NATO, but not vice versa. There ARE differences between the .223 Remington as shot in civilian rifles and the 5.56x45 in military use. While the external cartridge dimensions are essentially the same, the .223 Remington is built to SAAMI specs, rated to 50,000 CUP max pressure, and normally has a shorter throat. The 5.56x45 is built to NATO specs, rated to 60,000 CUP max pressure, and has a longer throat, optimized to shoot long bullets.

That said, there are various .223 Remington match chambers, including the Wylde chamber, that feature longer throats. Military 5.56x45 brass often, but not always, has thicker internal construction, and slightly less capacity than commercial .223 Rem brass. In 1977, NATO members signed an agreement to select a second, smaller caliber cartridge to replace the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge.

Of the cartridges tendered, the 5.56×45mm NATO was successful, but not the 55 gr M193 round used by the U.S. at that time. The wounds produced by the M193 round were so devastating that many consider it to be inhumane. Instead, the Belgian 62 gr SS109 round was chosen for standardization. This requirement made the SS109 round less capable of fragmentation than the M193 and was considered more humane.

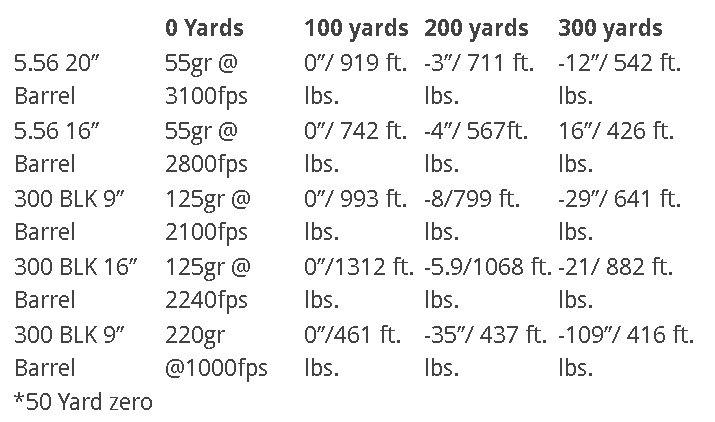

For short-range trajectory, we are going to compare our selected rounds out to a distance of 300 yards with the test firearms zeroed in at 100 yards. Data was generated by compiling the numbers from the manufacturer or by a ballistics calculator. With the ballistics calculator, we determined the short range trajectory by using each rounds bullet weight, muzzle velocity, and ballistic coefficient . Let's take a look at the recoil energy that is generated from our ten selected rounds and see if this trend holds up or if we see a little more variability. This data was generated using each rounds bullet weight, muzzle velocity, gun weight , and the powder charge. For the powder charge, we averaged several common powder loads from Nosler's load data and kept that charge constant for each round of the same cartridge.

These numbers might fluctuate slightly depending on the actual powder charge used by the manufacturer, but the trends between the cartridges should remain . The Belgian 62 gr SS109 round was chosen for standardization as the second NATO standard rifle cartridge which led to the October 1980 STANAG 4172. An actual helmet was not used for developmental testing, but an SAE 1010 or SAE 1020 mild steel plate, positioned to be struck at exactly 90 degrees.

It had a slightly lower muzzle velocity but better long-range performance due to higher sectional density and a superior drag coefficient. This requirement made the SS109 round less capable of fragmentation than the M193. Using 5.56 mm NATO mil-spec cartridges in a .223 Remington chambered rifle can lead to excessive wear and stress on the rifle and even be unsafe, and SAAMI recommends against the practice. The conflict in Afghanistan has caused a fundamental shift in the consideration of small-arms cartridge use.

Previously, the normal maximum range for small-arms engagements was around 300 meters. In Afghanistan, Taliban fighters with PKM machine guns and Dragunov SVD sniper rifles launched half their attacks between 300 and 900 meters. Over a quarter of engagements took place between 500 and 900 meters. British soldiers were initially only armed with 5.56 mm L85A2 rifles, L86A2 light support weapons, and L110A1 Para light machine guns.

The L85/86 had an effective range of 300 meters and the L110A1 had an effective range of 200–300 meters. Over half of small-arms engagements took place beyond the effective range of standard British infantry weapons, and 70 percent were beyond the effective range of a short barreled M4 Carbine. 5.56 mm rounds also have poor suppressive effects against concealed positions at those ranges. The suppressive effect of a small-arms bullet is directly proportional to the loudness of the sonic bang it generates, which in turn that is directly proportional to its size. 5.56 mm rounds have half the suppressive radius of 7.62 mm rounds, which can be further decreased by wind drift at long-range. Complaints are compounded by laboratory tests that reveal that 85 percent of SS109/M855 bullets do not yaw until at least 120 mm (4.7 in) of penetration, which would be most of the way through the body.

The U.S. Military had adopted for limited issue a 77-grain (5.0 g) "Match" bullet, type classified as the Mk 262. The heavy, lightly constructed bullet fragments more violently at short range and also has a longer fragmentation range. Originally designed for use in the Mk 12 SPR, the ammunition has found favor with special forces units who were seeking a more effective cartridge to fire from their M4A1 carbines.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.